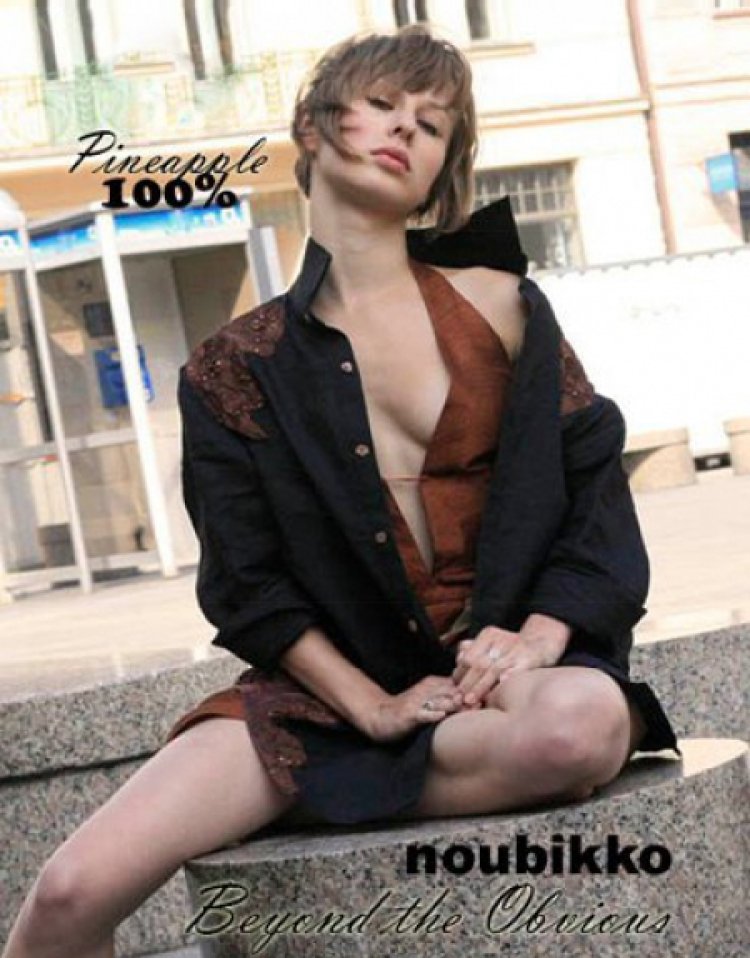

The Sky Is Everywhere

The biggest tragedy of “The Sky is Everywhere,” a YA dramedy about a young clarinet prodigy left reeling in the aftermath of her older sister’s sudden passing, is not the death that incites the story, so much as the misfortunate way in which it is told. The visual craftsmanship is stunning, and fans of director Josephine Decker’s work in particular might find something to enjoy here, but as a story it quickly buckles under its own weight. “The Sky is Everywhere” follows the bereaved Lennie (Grace Kaufman), a high school senior who rode her charismatic older sister Bailey’s (Havana Rose Liu) coattails so closely that Bailey’s recent death has thrown Lennie straight into a total identity crisis. She can’t even play a note on her formerly beloved clarinet and apathetically tosses aside her Juilliard dreams like last week’s trash, unceremoniously handing over the coveted first chair position to a catty rival. The only thing capable of competing with memories of Bailey for her attention is her massive crush on fellow band geek Joe (Jacques Colimon) and re-reading her favorite novel, Wuthering Heights. At home, Lennie avoids sharing her grief with her hippie, ever-so-slightly-witchy grandmother (Cherry Jones), who grows a rose garden that may or may not have preternatural aphrodisiac powers, or stoner Uncle Big (Jason Segel), who does not participate in the story so much as a exist in a strange pocket universe alongside it. Wearing Bailey’s old clothes and refusing to clean out Bailey’s belongings from their shared bedroom, Lennie clings to denial with all she has, and finds an ally in Bailey’s bereaved boyfriend Toby (Pico Alexander), previously her biggest rival for Bailey’s attention, sparking unexpected feelings. “It’s like you’re someone else and I don’t know if I like her,” Lennie’s best friend Sarah (Ji-young Yoo) tells her at a pivotal point in the film. Sarah’s characterization only goes as far as what can be extrapolated from her theater kid couture wardrobe, but still, in one of her few moments she sums up both the dramatic premise of the “The Sky is Everywhere” and why it fails to work: the film does such a poor job of painting a picture of who Lennie was before Bailey’s death that there’s no context to interpret who she has become, what that means, or why it matters. Josephine Decker ("Madeline’s Madeline," "Shirley") is a phenomenally talented director, and an unlikely pick for what is fundamentally a commercial-leaning teen romantic drama—the sort of unlikely combination of the high-risk, high-reward gamble that either strikes gold or like here, strikes out. Nonetheless, Decker and cinematographer Ava Berkofsky (best known for their work on “Insecure”) create a lot of beautiful images. Berkofsky’s particular eye for distinctive framing that shines so much in “Insecure” is on display here as well. But the execution is so polished, so sophisticated and intricate that it feels fundamentally at odds with the messiness of both youth and grief. The more avant-garde aspects of the film’s visual styling, from roses “coming to life” via dancers in green mesh bodysuits performing an interpretive number, to animated musical notes swirling through the air, are all presumably intended to put viewers in Lennie’s headspace. And yet it’s every shortcoming of the too-quirky-for-its-own-good “Me and Earl and the Dying Girl,” compounded by the fact that the techniques here generally lack significant thematic resonance. There are many beautiful sequences here that simply feel emotionally void. The extent to which Lennie’s headspace, particularly her recollections of Bailey, is stylized and curated has the unfortunate side effect of making everything feel detached and sterile. In Lennie’s memories, the lens through which all our access to Bailey is filtered, her sister is a manic pixie sunbeam who sings in her sleep and dances through streets and eats flowers—a beautiful but flat fantasy of a girl. Bailey feels unreal to a point where Lennie’s grief also begins to feel unreal; the void in her life, as she describes it, takes on an impossible shape. No actual person could have ever filled it. The young actors often come across a little at sea, and to be fair, Jason Segel does no better with a character so extraneous that his every appearance comes as something of a surprise. It’s really only Cherry Jones who manages to hold her own and not get swept away by the tidal waves of whimsy, retaining a grounded nature for her character that enables her to sell the film’s few compelling emotional beats. Jandy Nelson's script, an adaptation of her own novel, is like a wire hanger struggling to hold up the elaborate costume of the film’s baroque aesthetics. It's unfortunately a premier example of why self-adaptation can be quite risky—she’s so close to the story that she crams in an abundance of details at the expense of a compelling, more cohesive picture. The end result is that particularly crumbly kind of book-to-film a

The biggest tragedy of “The Sky is Everywhere,” a YA dramedy about a young clarinet prodigy left reeling in the aftermath of her older sister’s sudden passing, is not the death that incites the story, so much as the misfortunate way in which it is told. The visual craftsmanship is stunning, and fans of director Josephine Decker’s work in particular might find something to enjoy here, but as a story it quickly buckles under its own weight.

“The Sky is Everywhere” follows the bereaved Lennie (Grace Kaufman), a high school senior who rode her charismatic older sister Bailey’s (Havana Rose Liu) coattails so closely that Bailey’s recent death has thrown Lennie straight into a total identity crisis. She can’t even play a note on her formerly beloved clarinet and apathetically tosses aside her Juilliard dreams like last week’s trash, unceremoniously handing over the coveted first chair position to a catty rival. The only thing capable of competing with memories of Bailey for her attention is her massive crush on fellow band geek Joe (Jacques Colimon) and re-reading her favorite novel, Wuthering Heights.

At home, Lennie avoids sharing her grief with her hippie, ever-so-slightly-witchy grandmother (Cherry Jones), who grows a rose garden that may or may not have preternatural aphrodisiac powers, or stoner Uncle Big (Jason Segel), who does not participate in the story so much as a exist in a strange pocket universe alongside it. Wearing Bailey’s old clothes and refusing to clean out Bailey’s belongings from their shared bedroom, Lennie clings to denial with all she has, and finds an ally in Bailey’s bereaved boyfriend Toby (Pico Alexander), previously her biggest rival for Bailey’s attention, sparking unexpected feelings.

“It’s like you’re someone else and I don’t know if I like her,” Lennie’s best friend Sarah (Ji-young Yoo) tells her at a pivotal point in the film. Sarah’s characterization only goes as far as what can be extrapolated from her theater kid couture wardrobe, but still, in one of her few moments she sums up both the dramatic premise of the “The Sky is Everywhere” and why it fails to work: the film does such a poor job of painting a picture of who Lennie was before Bailey’s death that there’s no context to interpret who she has become, what that means, or why it matters.

Josephine Decker ("Madeline’s Madeline," "Shirley") is a phenomenally talented director, and an unlikely pick for what is fundamentally a commercial-leaning teen romantic drama—the sort of unlikely combination of the high-risk, high-reward gamble that either strikes gold or like here, strikes out. Nonetheless, Decker and cinematographer Ava Berkofsky (best known for their work on “Insecure”) create a lot of beautiful images. Berkofsky’s particular eye for distinctive framing that shines so much in “Insecure” is on display here as well.

But the execution is so polished, so sophisticated and intricate that it feels fundamentally at odds with the messiness of both youth and grief. The more avant-garde aspects of the film’s visual styling, from roses “coming to life” via dancers in green mesh bodysuits performing an interpretive number, to animated musical notes swirling through the air, are all presumably intended to put viewers in Lennie’s headspace. And yet it’s every shortcoming of the too-quirky-for-its-own-good “Me and Earl and the Dying Girl,” compounded by the fact that the techniques here generally lack significant thematic resonance.

There are many beautiful sequences here that simply feel emotionally void. The extent to which Lennie’s headspace, particularly her recollections of Bailey, is stylized and curated has the unfortunate side effect of making everything feel detached and sterile. In Lennie’s memories, the lens through which all our access to Bailey is filtered, her sister is a manic pixie sunbeam who sings in her sleep and dances through streets and eats flowers—a beautiful but flat fantasy of a girl. Bailey feels unreal to a point where Lennie’s grief also begins to feel unreal; the void in her life, as she describes it, takes on an impossible shape. No actual person could have ever filled it.

The young actors often come across a little at sea, and to be fair, Jason Segel does no better with a character so extraneous that his every appearance comes as something of a surprise. It’s really only Cherry Jones who manages to hold her own and not get swept away by the tidal waves of whimsy, retaining a grounded nature for her character that enables her to sell the film’s few compelling emotional beats.

Jandy Nelson's script, an adaptation of her own novel, is like a wire hanger struggling to hold up the elaborate costume of the film’s baroque aesthetics. It's unfortunately a premier example of why self-adaptation can be quite risky—she’s so close to the story that she crams in an abundance of details at the expense of a compelling, more cohesive picture. The end result is that particularly crumbly kind of book-to-film adaptation that comes across more like a SparkNotes you can watch, a story told at double-speed with much of its impact missing.

“The Sky is Everywhere” premieres on Apple TV+ and in theaters on February 11.