The Long Walk

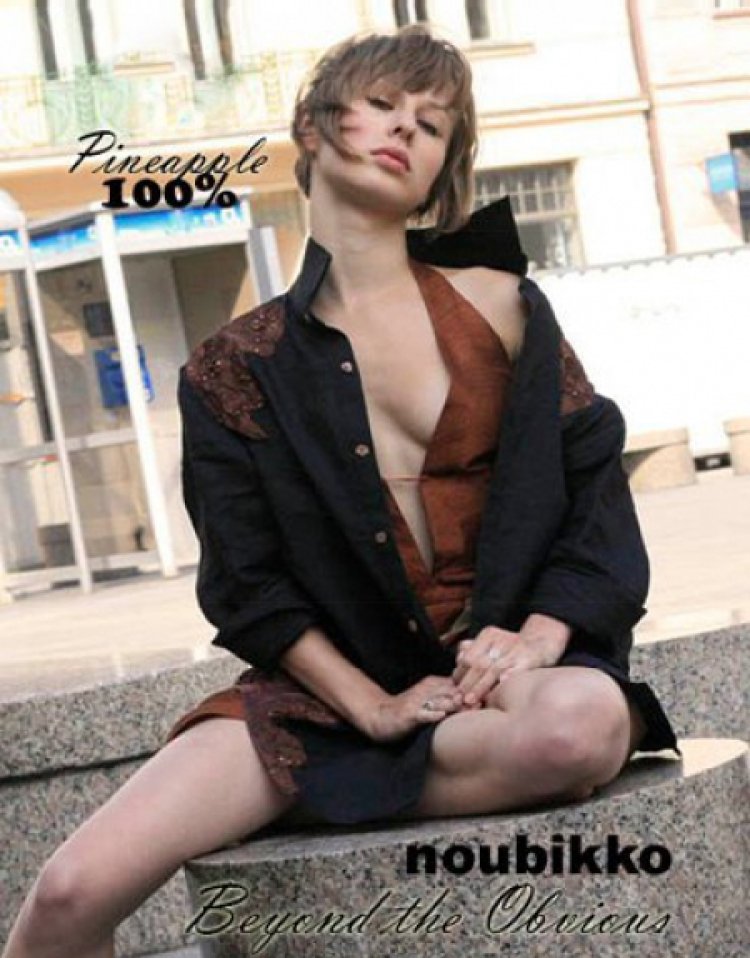

This is a story full of pain, full of wounds. It doesn’t register as such at first. But it eventually provides its own full rationale by doing so. "The Long Walk" begins as a story that’s very hard to pin down. Filmed in Laos, directed by American-born director of Laotian extraction Mattie Do, from a script by Christopher Larsen (who’s written all of Do’s three features), it’s set in a Laos village surrounded by woodland. In those woodlands an unnamed old man scavenges for wires, abandoned tech detritus, and so on. When he gets on the dirt road that bifurcates the woodland we see a modern cityscape ahead on the horizon. But the movie never gets there. Instead the man goes into the village to sell his gatherings. As he walks, a young woman appears next to him. “Fifty years and you’ve never said a word,” he says of their time on the road together. The silent woman isn’t even herself 50, or 40. In the village, the man needs to check something. He turns his arm and presses his wrist. From his skin a holographic read-out projects itself. The young shop clerk to whom he’s trying to pawn his woodland items laughs at him. “That the old government issue chip?” he laughs. “That must be a thousand years old.” Fifty years, a thousand years: what time is now in this movie anyway? The question is only going to become more convoluted as the scenario reveals the old man has a body in his dwelling. Soon after that, a young woman approaches the man and asks if he can talk to spirits. A young boy is introduced into the story line. He finds a different body, one that is resurrected as ... the same woman who walks silently with the old man down the long road. If you’re conversant with Chris Marker’s classic short film “La Jetée”—later expanded upon in a near-bombastic fashion in the Terry Gilliam feature “12 Monkeys”—you may have some idea of what’s going on here. But you only have some. Beyond its enigmatic and sometimes startling little frissons about the nature of time, “The Long Walk” also insists on poking the porous boundaries between science and the supernatural, or the spiritual. It also has plenty to sit with about the ideas of guilt and of responsibility, and the fact that it's set and shot in Laos means that it’s considering those themes on a world-historical level. Yannawoutthi Chanthalungsy, as the old man, has a kind of settled unease that suggests the great American actor Robert Forster. You need only take in his grave face to know that his character is a man of secrets. Those secrets derive from what was his very misguided sense of duty, and it is when they come to light that the movie opens up the totality of its pain-filled world. This is a nuanced film, one that doesn’t lay itself out in what we would consider a satisfyingly linear fashion. But it’s the sort of thing that gets a grip on your spine when you’re least expecting it. Now playing in theaters and available on VOD on March 1.

This is a story full of pain, full of wounds. It doesn’t register as such at first. But it eventually provides its own full rationale by doing so.

"The Long Walk" begins as a story that’s very hard to pin down. Filmed in Laos, directed by American-born director of Laotian extraction Mattie Do, from a script by Christopher Larsen (who’s written all of Do’s three features), it’s set in a Laos village surrounded by woodland. In those woodlands an unnamed old man scavenges for wires, abandoned tech detritus, and so on. When he gets on the dirt road that bifurcates the woodland we see a modern cityscape ahead on the horizon. But the movie never gets there.

Instead the man goes into the village to sell his gatherings. As he walks, a young woman appears next to him. “Fifty years and you’ve never said a word,” he says of their time on the road together. The silent woman isn’t even herself 50, or 40.

In the village, the man needs to check something. He turns his arm and presses his wrist. From his skin a holographic read-out projects itself. The young shop clerk to whom he’s trying to pawn his woodland items laughs at him. “That the old government issue chip?” he laughs. “That must be a thousand years old.”

Fifty years, a thousand years: what time is now in this movie anyway? The question is only going to become more convoluted as the scenario reveals the old man has a body in his dwelling. Soon after that, a young woman approaches the man and asks if he can talk to spirits. A young boy is introduced into the story line. He finds a different body, one that is resurrected as ... the same woman who walks silently with the old man down the long road.

If you’re conversant with Chris Marker’s classic short film “La Jetée”—later expanded upon in a near-bombastic fashion in the Terry Gilliam feature “12 Monkeys”—you may have some idea of what’s going on here. But you only have some. Beyond its enigmatic and sometimes startling little frissons about the nature of time, “The Long Walk” also insists on poking the porous boundaries between science and the supernatural, or the spiritual. It also has plenty to sit with about the ideas of guilt and of responsibility, and the fact that it's set and shot in Laos means that it’s considering those themes on a world-historical level.

Yannawoutthi Chanthalungsy, as the old man, has a kind of settled unease that suggests the great American actor Robert Forster. You need only take in his grave face to know that his character is a man of secrets. Those secrets derive from what was his very misguided sense of duty, and it is when they come to light that the movie opens up the totality of its pain-filled world. This is a nuanced film, one that doesn’t lay itself out in what we would consider a satisfyingly linear fashion. But it’s the sort of thing that gets a grip on your spine when you’re least expecting it.

Now playing in theaters and available on VOD on March 1.