The Worst Person in the World

There’s a restlessness that arises within when, by society’s punitive standards, one’s youth begins inevitably fading away. As you perform the taxing charade of adulthood, with your twenties now concluded and your thirties ticking down, the urgency to become, to achieve, to fall in love forever, all to prove you’ve got something to show for your earthbound time, settles in. The feeling that the burning light of promise is quickly extinguishing, consumed by the status quo-imposed milestones, drives Norwegian director Joachim Trier’s phenomenally inventive dramedy “The Worst Person in the World,” the third installment in his unplanned, yet spiritually akin Oslo Trilogy. “I feel like a spectator in my own life,” say Julie (Renate Reinsve), a young woman still piecing together the spectrum of her emotional wants and needs. She explains this to Aksel (Anders Danielsen Lie), her lover who is over a decade her senior. In Julie, millennial anxiety manifests in flares of frustration and feeling stuck as she wrestles with self-discovery. Segmented into a dozen chapters (plus a prologue and an epilogue), the literary-structured film introduces Julie with a montage of her college days trapped in a swirl of indecisiveness and exploration, between career path changes and romantic flings. But by the end of the first act, Julie will turn 30 and be faced with the looming question of potential motherhood. Trier and his longtime co-writer Eskil Vogt constantly invigorate our understanding of Julie and her romantic partners via insightful visual digressions guided by the voice of a female narrator. Soaked in Harry Nilsson’s deceivingly cheerful songs, their high-spirited narrative language finds an ideal vehicle in the way cinematographer Kasper Tuxen suffuses the characters’ genuine visages with the softest, most elegant lighting of the Nordic skies. Working at a bookstore, after dabbling in medicine and photography, Julie is now in the shadow of Aksel, a revered cartoonist of politically incorrect material. He’s a safe choice, a reasonable partner, but she is not ready for the commitment he desires. A montage adds to the feeling that she’s behind on life’s schedule, showing how the women in her lineage across generations were already raising children at her age. Part of Julie’s growth in the gracefully whimsical “The Worst Person in the World,” as she navigates an estrangement from her father, comes from moments about her fortitude to step away from a situation or a person in order to pursue her own happiness. There’s an agency in her perceived recklessness that places her in a limbo between juvenile hedonism and expected maturity. Yet, in addressing the necessary selfishness to let herself move along based on her intuitiveness, she shows a deep compassion for the human being on the other side of every schism. It’s in those scenes where Julie and Aksel air out the sorrow for the things that might never come to pass between them, that Trier captures an almost shocking display of honesty, rid of any defensive armor. Here are two people that love each other, who can come to terms with the impossibility of their union at this moment in time. Reinsve’s performance is an incantation of the highest caliber, an act of pure acting magic that fluctuates across Julie’s evolving arc. By allowing us to observe the character over time and in distinct facets, Trier gives Reinsve a platform not only to show range but also to construct a character in small, but immensely telling emotional modulations: her faint smile when trying not to cry or an uncontainable grin of joy, her dancing with abandon, or the way she stands her ground with a devastating determination. Through her, Julie comes of age at her own pace. She often runs towards something that’s impermanent but exciting, only to discover that maybe she has been looking for answers in the arms of another when they've always been only hers to formulate. To think Reinsve didn’t break out in the 10 years between her first on-screen appearance in Trier’s “Oslo, August 31st” is outrageous. But in a sense, that period of trying to breakthrough and not accomplishing it until her early thirties may have created a kinship with her fictional persona. Danielsen Lie conveys a similar sweetness as Aksel, even as a man unwilling to let go of the obsolete. There’s also an embarrassingly recognizable fear in him of losing one’s edge, of learning that all the sensible apprehensions we once mocked have begun keeping us up at night. Aksel’s speech about how at some point all we have left is to look back at who we were, to the artifacts of youth, is a striking gut-punch. In those pensive duels of sincerity that Trier stages between the impeccable Danielsen Lie and the mesmerizing Reinsve, the actor repeatedly puts on a smile that appears as if his cheekbones are dams fighting to holds back a flood of tears. There’s a desperate pleading in his eyes that reads almost childlike, confessing that hi

There’s a restlessness that arises within when, by society’s punitive standards, one’s youth begins inevitably fading away. As you perform the taxing charade of adulthood, with your twenties now concluded and your thirties ticking down, the urgency to become, to achieve, to fall in love forever, all to prove you’ve got something to show for your earthbound time, settles in.

The feeling that the burning light of promise is quickly extinguishing, consumed by the status quo-imposed milestones, drives Norwegian director Joachim Trier’s phenomenally inventive dramedy “The Worst Person in the World,” the third installment in his unplanned, yet spiritually akin Oslo Trilogy.

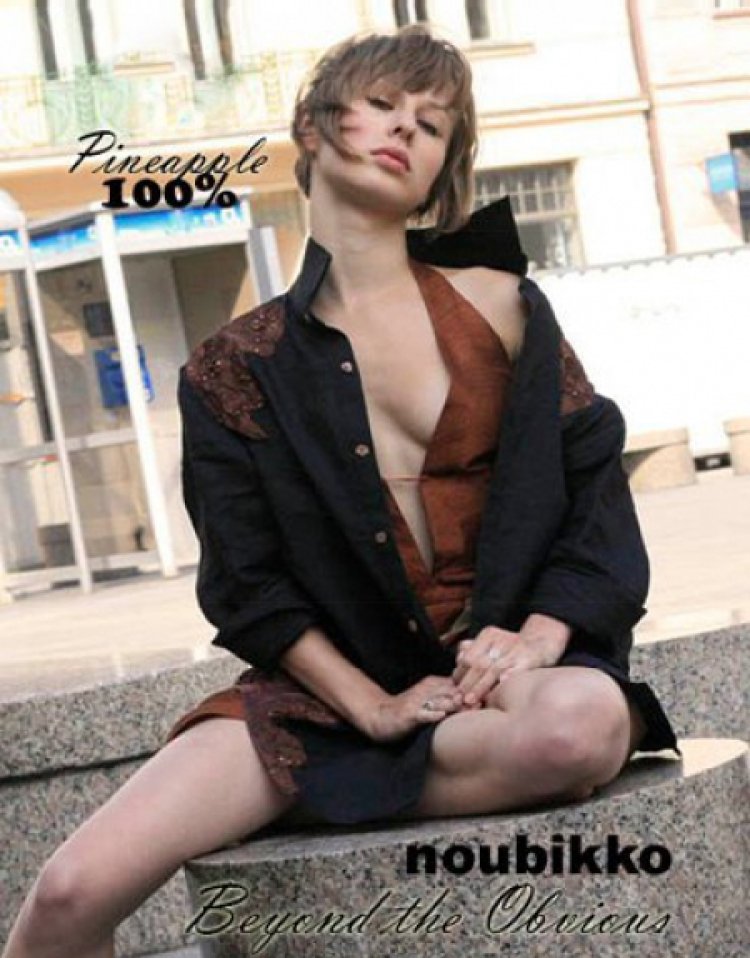

“I feel like a spectator in my own life,” say Julie (Renate Reinsve), a young woman still piecing together the spectrum of her emotional wants and needs. She explains this to Aksel (Anders Danielsen Lie), her lover who is over a decade her senior. In Julie, millennial anxiety manifests in flares of frustration and feeling stuck as she wrestles with self-discovery.

Segmented into a dozen chapters (plus a prologue and an epilogue), the literary-structured film introduces Julie with a montage of her college days trapped in a swirl of indecisiveness and exploration, between career path changes and romantic flings. But by the end of the first act, Julie will turn 30 and be faced with the looming question of potential motherhood.

Trier and his longtime co-writer Eskil Vogt constantly invigorate our understanding of Julie and her romantic partners via insightful visual digressions guided by the voice of a female narrator. Soaked in Harry Nilsson’s deceivingly cheerful songs, their high-spirited narrative language finds an ideal vehicle in the way cinematographer Kasper Tuxen suffuses the characters’ genuine visages with the softest, most elegant lighting of the Nordic skies.

Working at a bookstore, after dabbling in medicine and photography, Julie is now in the shadow of Aksel, a revered cartoonist of politically incorrect material. He’s a safe choice, a reasonable partner, but she is not ready for the commitment he desires. A montage adds to the feeling that she’s behind on life’s schedule, showing how the women in her lineage across generations were already raising children at her age.

Part of Julie’s growth in the gracefully whimsical “The Worst Person in the World,” as she navigates an estrangement from her father, comes from moments about her fortitude to step away from a situation or a person in order to pursue her own happiness. There’s an agency in her perceived recklessness that places her in a limbo between juvenile hedonism and expected maturity.

Yet, in addressing the necessary selfishness to let herself move along based on her intuitiveness, she shows a deep compassion for the human being on the other side of every schism. It’s in those scenes where Julie and Aksel air out the sorrow for the things that might never come to pass between them, that Trier captures an almost shocking display of honesty, rid of any defensive armor. Here are two people that love each other, who can come to terms with the impossibility of their union at this moment in time.

Reinsve’s performance is an incantation of the highest caliber, an act of pure acting magic that fluctuates across Julie’s evolving arc. By allowing us to observe the character over time and in distinct facets, Trier gives Reinsve a platform not only to show range but also to construct a character in small, but immensely telling emotional modulations: her faint smile when trying not to cry or an uncontainable grin of joy, her dancing with abandon, or the way she stands her ground with a devastating determination.

Through her, Julie comes of age at her own pace. She often runs towards something that’s impermanent but exciting, only to discover that maybe she has been looking for answers in the arms of another when they've always been only hers to formulate. To think Reinsve didn’t break out in the 10 years between her first on-screen appearance in Trier’s “Oslo, August 31st” is outrageous. But in a sense, that period of trying to breakthrough and not accomplishing it until her early thirties may have created a kinship with her fictional persona.

Danielsen Lie conveys a similar sweetness as Aksel, even as a man unwilling to let go of the obsolete. There’s also an embarrassingly recognizable fear in him of losing one’s edge, of learning that all the sensible apprehensions we once mocked have begun keeping us up at night. Aksel’s speech about how at some point all we have left is to look back at who we were, to the artifacts of youth, is a striking gut-punch.

In those pensive duels of sincerity that Trier stages between the impeccable Danielsen Lie and the mesmerizing Reinsve, the actor repeatedly puts on a smile that appears as if his cheekbones are dams fighting to holds back a flood of tears. There’s a desperate pleading in his eyes that reads almost childlike, confessing that his artistic wins didn’t dilute the consternation for finding meaning in the sum of his mortal days.

Each chapter in “The Worst Person in the World” feels like a complete, unique thought encapsulating something real in unrealistic visual terms—like the tracks on an eclectic album, which even if they vary in tone comprise a cohesive whole. With Tuxen and editor Olivier Bugge Coutté embellishing the playfulness of the screenplay, Trier conceives highly stimulating instances such as with the agile camera movements that accompany Aksel as he plays air drums in a musical driven trance, or in the hilarious bizarreness of a drug-induced trip that features splashes of animation.

A prime example of Trier’s cinematic ebullience is a sequence where Julie meets Eivind (Herbert Nordrum), a new lover. Both promise not to cheat on their partners with each other, but the pair engage in a flirtatious dance of intimacy that surpasses the carnal. Later, she dreams of making time stand still to traverse Oslo for a kiss and an afternoon of wonder, in one of the film’s most fabulous displays of romanticism laden with the thrill of mischief.

Trier and Vogt are poets of this longing for what’s to come while trapped in a convoluted present, and have revisited this idea across their work, especially in their Oslo-set escapades. In “Reprise,” the young authors discover that success doesn’t equal fulfillment, while in the more somber “Oslo, August 31st” an addict in his thirties sees no reason to continue having disappointment. That they can still engage so intensely with this disquieting state so familiar to many is a sensational virtue.

“The Worst Person in the World,” Trier’s stirringly sophisticated masterpiece, unrolls in piecemeal manner, but once fully extended is a tapestry of unfeigned experiences sowed with the thread of truth, in all its painful ambivalence. All it can confirm is that there’s probably no turning point in which life is supposed to start for good.

For our transient time here—an inharmonious symphony of beginnings and conclusions, small triumphs and big disillusions, all without a grand design—perhaps the plans that fell through, Julie’s and ours, don’t matter as much. The value is in the bravery to see the crumbles of a former dream or a past relationship and still try again in earnest from scratch; to be aware that the same mistakes may come along and that growing pains may never vanish, to embrace that we are on nobody’s timeline but our own.

Now playing in select theaters.