Ted K

“Ted K” trumpets its authentic bona fides early, informing us in an opening crawl that it was shot on the actual Montana land where Ted Kaczynski’s 10-by-12-foot cabin once stood, where he lived his spartan life and crafted the manifesto that would earn him the moniker The Unabomber. We also learn that director Tony Stone and his co-writers, Gaddy Davis and John Rosenthal, used Kaczynski’s own words from his 25,000 pages of writing to build their script. The Unabomber viewed the encroachment of technology as a crucial force in destroying the natural world. He wrote about it, he raged about it. He’s currently serving a life sentence in federal prison for his deadly efforts to stop it. Lest we have any doubt about his philosophy, we hear him lay it out in an opening voiceover from star Sharlto Copley: “Modern technology is the worst thing that ever happened to the world, and to promote its progress is nothing short of criminal.” And of course, the Washington Post published his manifesto in June 1995 in hopes of preventing further terrorist violence. And yet, while Copley is on screen for nearly the entirety of “Ted K,” which follows Kaczynski in the years leading up to his arrest, the man himself remains inherently unknowable—fearsome and fascinating but just out of reach. His performance is tightly coiled and increasingly twitchy as Ted struggles to maintain his composure and dares to execute more and more violent acts against those he views as his aggressors. “I have a plan for revenge,” he says in the nasally narration of his journals. “I want to kill some people, preferably a scientist, a communist, businessman or some other big shot.” What he thinks is clear; who he is, less so. That’s probably by design. Despite the shocking acts on display in “Ted K,” we feel like we’re in a bit of a haze as we wander the woods with Kaczynski, watching him run shirtless and shoot at helicopters. Stone favors the subtlest of pushes into his subject matter, or uses slow-motion to contrast with the significance of a moment of truth, as when Kaczynski mails off one of his deadly, explosive packages with Alice in Chains’ “Rooster” blaring in the background. The noise of chopping, sawing, and shearing from the nearby logging industry creates a pesky rhythm. And the droning, synth score from British composer Benjamin John Power, known as Blanck Mass, adds greatly to the film’s overall hypnotic vibe. Just as the din surrounding Kaczynski swells to a panicky cacophony, so, too, do the music and sound design grow to heighten our feeling of anxiety. But some of the tensest moments in the film are actually the most mundane, as when Kaczynski confronts a phone company clerk about losing coins in the pay phone. An airplane crosses the blue sky overhead, shattering the reverie of his peace and quiet, and you can feel the anger rising within him. And a seemingly innocuous trip to the local library reveals that he’s looking up the names and addresses of tech executives to target them. Increasingly, though, Stone relies on fantasy sequences to signify Kaczynski’s break with reality and sanity, which feels unnecessary. We see a pretty and pleasant woman named Becky (Amber Rose Mason) who appears magically and just happens to be interested in all the things he likes to do, such as bike riding and fishing. We already know he’s lonely—he complains about how little experience he’s had with women in his agitated, one-sided phone calls with his mother and brother—but the arrival of this sunny, imaginary figure into Kaczynski’s moody cocoon becomes a distraction. Still, Copley’s performance remains riveting throughout. It’s a testament to his delivery and physicality that we can hear Kaczynski speak expansively about what he’s going to do, and we can watch him experiment with various explosives, and we’re still on edge, wondering what might happen. His squirrelly nature makes him unpredictable, even as he sits quietly in his cozy cabin, listening to classical music on the Montana NPR station, planning who he’ll try to kill next. Now playing in theaters and available on demand.

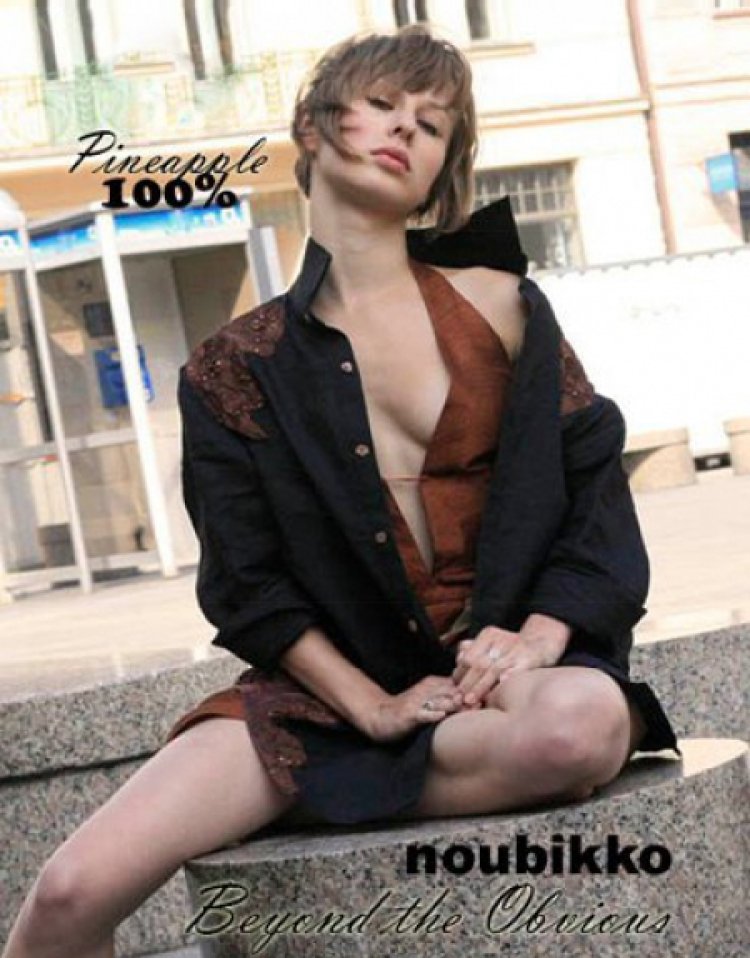

“Ted K” trumpets its authentic bona fides early, informing us in an opening crawl that it was shot on the actual Montana land where Ted Kaczynski’s 10-by-12-foot cabin once stood, where he lived his spartan life and crafted the manifesto that would earn him the moniker The Unabomber. We also learn that director Tony Stone and his co-writers, Gaddy Davis and John Rosenthal, used Kaczynski’s own words from his 25,000 pages of writing to build their script.

The Unabomber viewed the encroachment of technology as a crucial force in destroying the natural world. He wrote about it, he raged about it. He’s currently serving a life sentence in federal prison for his deadly efforts to stop it. Lest we have any doubt about his philosophy, we hear him lay it out in an opening voiceover from star Sharlto Copley: “Modern technology is the worst thing that ever happened to the world, and to promote its progress is nothing short of criminal.” And of course, the Washington Post published his manifesto in June 1995 in hopes of preventing further terrorist violence.

And yet, while Copley is on screen for nearly the entirety of “Ted K,” which follows Kaczynski in the years leading up to his arrest, the man himself remains inherently unknowable—fearsome and fascinating but just out of reach. His performance is tightly coiled and increasingly twitchy as Ted struggles to maintain his composure and dares to execute more and more violent acts against those he views as his aggressors. “I have a plan for revenge,” he says in the nasally narration of his journals. “I want to kill some people, preferably a scientist, a communist, businessman or some other big shot.” What he thinks is clear; who he is, less so.

That’s probably by design. Despite the shocking acts on display in “Ted K,” we feel like we’re in a bit of a haze as we wander the woods with Kaczynski, watching him run shirtless and shoot at helicopters. Stone favors the subtlest of pushes into his subject matter, or uses slow-motion to contrast with the significance of a moment of truth, as when Kaczynski mails off one of his deadly, explosive packages with Alice in Chains’ “Rooster” blaring in the background. The noise of chopping, sawing, and shearing from the nearby logging industry creates a pesky rhythm. And the droning, synth score from British composer Benjamin John Power, known as Blanck Mass, adds greatly to the film’s overall hypnotic vibe. Just as the din surrounding Kaczynski swells to a panicky cacophony, so, too, do the music and sound design grow to heighten our feeling of anxiety.

But some of the tensest moments in the film are actually the most mundane, as when Kaczynski confronts a phone company clerk about losing coins in the pay phone. An airplane crosses the blue sky overhead, shattering the reverie of his peace and quiet, and you can feel the anger rising within him. And a seemingly innocuous trip to the local library reveals that he’s looking up the names and addresses of tech executives to target them.

Increasingly, though, Stone relies on fantasy sequences to signify Kaczynski’s break with reality and sanity, which feels unnecessary. We see a pretty and pleasant woman named Becky (Amber Rose Mason) who appears magically and just happens to be interested in all the things he likes to do, such as bike riding and fishing. We already know he’s lonely—he complains about how little experience he’s had with women in his agitated, one-sided phone calls with his mother and brother—but the arrival of this sunny, imaginary figure into Kaczynski’s moody cocoon becomes a distraction.

Still, Copley’s performance remains riveting throughout. It’s a testament to his delivery and physicality that we can hear Kaczynski speak expansively about what he’s going to do, and we can watch him experiment with various explosives, and we’re still on edge, wondering what might happen. His squirrelly nature makes him unpredictable, even as he sits quietly in his cozy cabin, listening to classical music on the Montana NPR station, planning who he’ll try to kill next.

Now playing in theaters and available on demand.