Great Freedom

Franz Rogowski is one of the great leading men in world cinema—the kind of actor you're always glad to see. His intensity, physical commitment and internalized qualities recall the young Robert DeNiro in that incredible period that stretched from "Mean Streets" through "The King of Comedy." But he also has the warmth and instant accessibility that we associate with old movie stars. He never hands you anything, but you never feel as if you have to struggle to discern the complex emotions that his characters are feeling. In "Great Freedom," Rogowski stars as Hans, a gay Jewish man sentenced to Austrian prison after World War II for violating anti-homosexuality laws. It's one of his most moving and fully imagined performances, anchoring a drama that tries to do a bit too much for its own good in terms of structure. Director-cowriter Sebastian Meise’s script jumps between periods over the span of decades, at times confusingly, with the characters' grooming and relative amounts of grey situating us, and even though you can see the justification for it, it fractures and abstracts the through-line of the main character's evolution, trading intellectuality for feeling. But the characterizations and performances are so exact and restrained—rooting their insights in actions and reactions rather than constantly announce what's happening in the characters' hearts—that the result is affecting and often wrenching cinema, about outsiders struggling to survive in a society that hates them and wants them to suffer. The opening credits show Hans taking part in sexual encounters that will become part of his rap sheet. These are imagined by Meise and his co-screenwriter Thomas Reider as mid-twentieth century porno films shot with a home movie camera, which gives them a keepsake quality. Sentenced for violating Paragraph 175, which forbade the expression of homosexual desire, he's sent to prison, and the movie takes its time revealing that throughout the course of his life, he would keep returning there, being unable to repress who he is. We also find out that Hans is Jewish, and that he his first sentence for violating Paragraph 175 was handed down immediately after his release from a concentration camp. The tattoos on his forearms become an integral part of one his two most important relationships behind bars. Hans' cellmate, Viktor (Georg Friedrich), is a virulent homophobe who starts treating him like a pariah as soon as he learns why he's behind bars. Viktor is an outcast of a different sort, doing time for drug offenses. Channeling the writing of both Jean Genet and William S. Burroughs, the movie establishes an imaginative affinity between forbidden desire and addiction. This could be a problematic and potentially offensive juxtaposition if it weren't treated with such delicacy, like something out of a fable. The point is that neither of these men can turn off who they are, and it's not their fault that the state refuses to engage with and accept them instead of locking them away and torturing their bodies and spirits. Any early concern that the movie is about to turn into a sort of gay Austrian prison version of "Green Book," about a bigot who reforms after spending time with a saintly representative of The Other, fades when you get to know the men and see how they act towards each other and their environment. Viktor and Hans use their shared dexterity with, and access to, needles (Viktor is junkie, while Hans works in the prison sweatshop) to contrive a homemade tattoo kit that Viktor uses to crudely obliterate Hans' concentration camp numbers. Their team-up in hiding evidence of this act of decency bonds them, putting them in cahoots against prison guards who are determined to punish any display of individuality or basic empathy by beating prisoners with truncheons and locking them away in solitary confinement (a misery conveyed by briefly plunging viewers into absolute darkness, which is surely more powerful in a movie theater than at home where you're surrounded by reminders that at least you the viewer are okay). The film's other major relationship, between Hans and a younger inmate, Leo (Anton von Lucke), is just as affecting though considerably less fraught, at times getting close to a flat-out romantic love story that just happens to occur in one of the worst places imaginable. It's in these scenes that "Great Freedom" is at its most imaginative, showing how the men acknowledge and communicate their desire for each other and act on it in ways that will satisfy their need for sex and partnership while minimizing the chance that the authorities will catch on. The incarcerated person's acquired skill at sending coded messages and finding secret spaces to be free is shown in furtive conversations, the concoction and hatching of plans, and fleeting instants of bliss that are all the more inspiring for having been devised in a man-made Hell. Through it all, Rogowski is the audience's guide and surrogate, sometimes

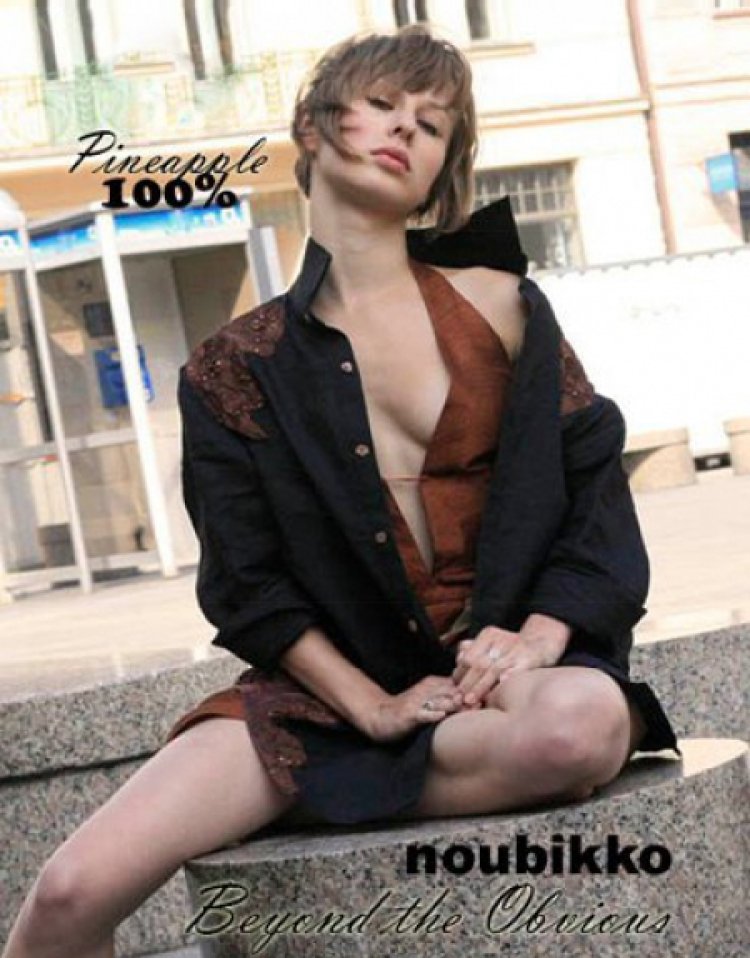

Franz Rogowski is one of the great leading men in world cinema—the kind of actor you're always glad to see. His intensity, physical commitment and internalized qualities recall the young Robert DeNiro in that incredible period that stretched from "Mean Streets" through "The King of Comedy." But he also has the warmth and instant accessibility that we associate with old movie stars. He never hands you anything, but you never feel as if you have to struggle to discern the complex emotions that his characters are feeling.

In "Great Freedom," Rogowski stars as Hans, a gay Jewish man sentenced to Austrian prison after World War II for violating anti-homosexuality laws. It's one of his most moving and fully imagined performances, anchoring a drama that tries to do a bit too much for its own good in terms of structure. Director-cowriter Sebastian Meise’s script jumps between periods over the span of decades, at times confusingly, with the characters' grooming and relative amounts of grey situating us, and even though you can see the justification for it, it fractures and abstracts the through-line of the main character's evolution, trading intellectuality for feeling. But the characterizations and performances are so exact and restrained—rooting their insights in actions and reactions rather than constantly announce what's happening in the characters' hearts—that the result is affecting and often wrenching cinema, about outsiders struggling to survive in a society that hates them and wants them to suffer.

The opening credits show Hans taking part in sexual encounters that will become part of his rap sheet. These are imagined by Meise and his co-screenwriter Thomas Reider as mid-twentieth century porno films shot with a home movie camera, which gives them a keepsake quality. Sentenced for violating Paragraph 175, which forbade the expression of homosexual desire, he's sent to prison, and the movie takes its time revealing that throughout the course of his life, he would keep returning there, being unable to repress who he is.

We also find out that Hans is Jewish, and that he his first sentence for violating Paragraph 175 was handed down immediately after his release from a concentration camp. The tattoos on his forearms become an integral part of one his two most important relationships behind bars. Hans' cellmate, Viktor (Georg Friedrich), is a virulent homophobe who starts treating him like a pariah as soon as he learns why he's behind bars. Viktor is an outcast of a different sort, doing time for drug offenses.

Channeling the writing of both Jean Genet and William S. Burroughs, the movie establishes an imaginative affinity between forbidden desire and addiction. This could be a problematic and potentially offensive juxtaposition if it weren't treated with such delicacy, like something out of a fable. The point is that neither of these men can turn off who they are, and it's not their fault that the state refuses to engage with and accept them instead of locking them away and torturing their bodies and spirits.

Any early concern that the movie is about to turn into a sort of gay Austrian prison version of "Green Book," about a bigot who reforms after spending time with a saintly representative of The Other, fades when you get to know the men and see how they act towards each other and their environment. Viktor and Hans use their shared dexterity with, and access to, needles (Viktor is junkie, while Hans works in the prison sweatshop) to contrive a homemade tattoo kit that Viktor uses to crudely obliterate Hans' concentration camp numbers. Their team-up in hiding evidence of this act of decency bonds them, putting them in cahoots against prison guards who are determined to punish any display of individuality or basic empathy by beating prisoners with truncheons and locking them away in solitary confinement (a misery conveyed by briefly plunging viewers into absolute darkness, which is surely more powerful in a movie theater than at home where you're surrounded by reminders that at least you the viewer are okay).

The film's other major relationship, between Hans and a younger inmate, Leo (Anton von Lucke), is just as affecting though considerably less fraught, at times getting close to a flat-out romantic love story that just happens to occur in one of the worst places imaginable. It's in these scenes that "Great Freedom" is at its most imaginative, showing how the men acknowledge and communicate their desire for each other and act on it in ways that will satisfy their need for sex and partnership while minimizing the chance that the authorities will catch on. The incarcerated person's acquired skill at sending coded messages and finding secret spaces to be free is shown in furtive conversations, the concoction and hatching of plans, and fleeting instants of bliss that are all the more inspiring for having been devised in a man-made Hell.

Through it all, Rogowski is the audience's guide and surrogate, sometimes a terrified newbie and other times a wizened lifer, always seeming to accept the day-to-day and try to find peace and love in it, despite the constant reminders that Hans' body belongs to the state. Even when he finds a way to put it to his own uses, the resulting moments of happiness are taking place on borrowed time.

It's not easy to put across the energy that Rogowski does here (basically, battered but indestructible childlike innocence and pure romantic longing) without going soggy and corny. How does he do it? Mainly by never doing more than he needs to in order to communicate what we need to know. Rogowski makes the audience come to him, but never seems coy or withholding.

That the viewer can fully comprehend every aspect of Hans' complex psychology after having made only minimal effort syncs up nicely with the main message of Hans and Viktor's relationship, which is that you don't have to try all that hard to find common ground with another person, no matter how seemingly alien to your own sensibilities. You need only recognize them as a fellow human being who's doing the best they can, one day at a time.