Ancient DNA sheds light on origins of 7,000-year-old Saharan mummies

Today, the view from the Takarkori rock shelter in southwestern Libya is of endless sandy dunes and barren rock, but 7,000 years ago, this region of the Sahara Desert was a far lusher, hospitable place.

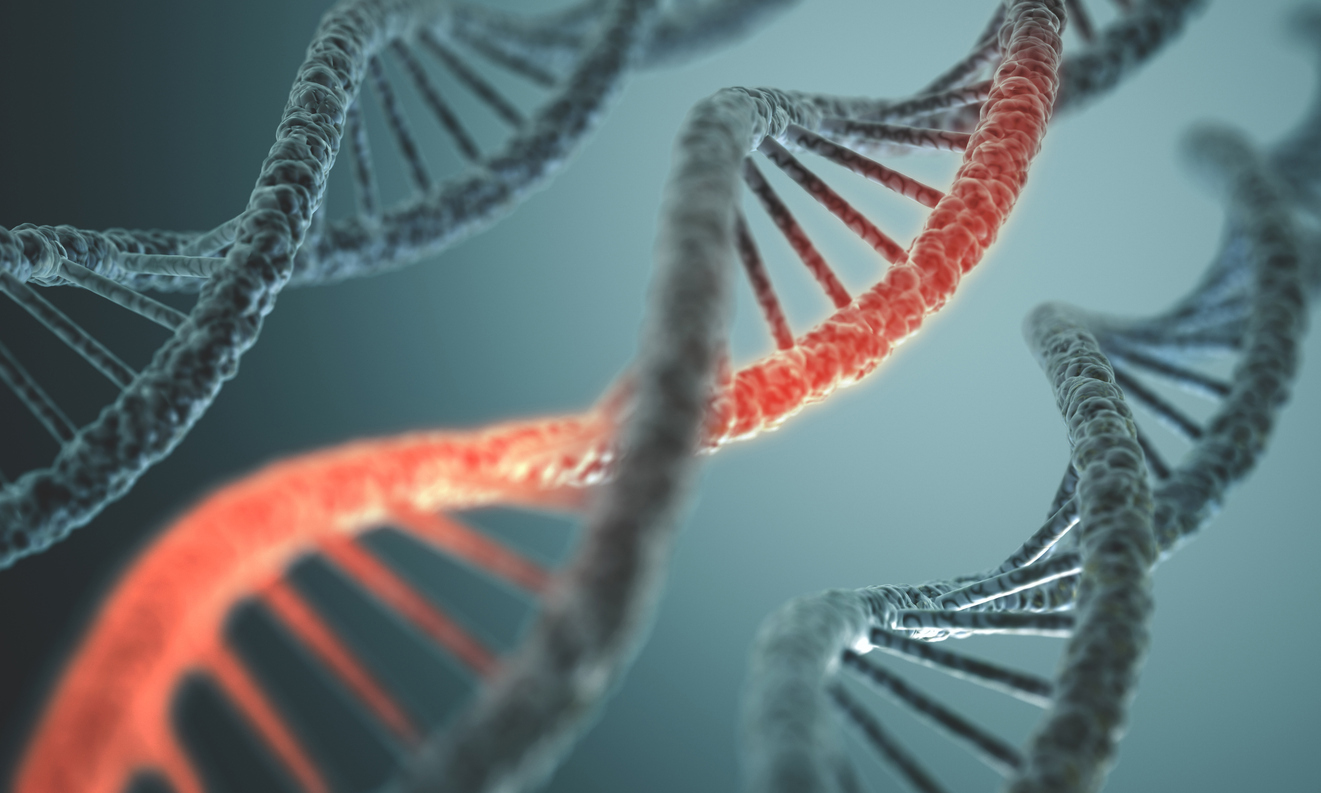

Now, scientists aiming to understand the origins of inhabitants of the "green Sahara" say they have managed to recover the first whole genomes — detailed genetic information — from the remains of two women buried at Takarkori.

In the distant past, the area was a verdant savanna with trees, permanent lakes and rivers that supported large animals such as hippopotamuses and elephants.

READ MORE: This is the dubious way Trump calculated his 'reciprocal' tariffs

It was also home to early human communities, including 15 women and children archaeologists found buried at the rock shelter, that lived off fish and herded sheep and goats.

"We started with these two (skeletons) because they are very well-preserved — the skin, ligaments, tissues," said Savino di Lernia, coauthor of the new study published Wednesday in the journal Nature.

The findings mark the first time archaeologists have managed to sequence whole genomes from human remains found in such a hot and arid environment, said di Lernia, an associate professor of African archaeology and ethnoarchaeology at Sapienza University of Rome.

The genomic analysis yielded surprises for the study team, revealing that the inhabitants of the green Sahara were a previously unknown and long-isolated population that had likely occupied the region for tens of thousands of years.

Mummies reveal secrets of the Sahara's past

Excavation of the Takarkori rock shelter, reachable only by a four-wheel drive vehicle, started in 2003, with the two female mummies among the first finds.

"We found the first mummy on the second day of the excavation," di Lernia recalled.

"We scratched the sand and found the mandible."

The small community that made its home at the rock shelter possibly migrated there with humankind's first big push out of Africa more than 50,000 years ago.

READ MORE: This is the dubious way Trump calculated his 'reciprocal' tariffs

Study coauthor Harald Ringbauer said it was unusual to encounter such an isolated genetic ancestry, especially compared with Europe, where there was much more mixing.

Ringbauer is a researcher and group leader of archaeogenetics at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, which has pioneered techniques to receive genetic material from old bones and fossils.

This genetic isolation, the authors of the study reasoned, suggested the region likely wasn't a migration corridor that linked sub-Saharan Africa to Northern Africa despite the Sahara's hospitable conditions at the time.

Past analyses of cave paintings and animal remains found at archaeological sites across the Sahara have suggested its inhabitants were pastoralists who herded sheep, goats or cattle, prompting some researchers to hypothesize the herders spread from the Near East where farming originated.

However, such migration was unlikely, given the genetic isolation of the Takarkori group, the authors of the new report suggested.

READ MORE: Measles cases hit 28-year high in Europe, UN, WHO say

Instead, the study team hypothesized, pastoralism was adopted via a process of cultural exchange, such as interaction with other groups that already raised domesticated animals.

"We know now that they were isolated in terms of genetics, but not in cultural terms," di Lernia said.

There's a lot of networks that we know from several parts of the continent, because we have pottery coming from sub-Saharan Africa.

We have pottery coming from the Nile Valley and the like."

"They had this kind of lineage, which is quite ancestral, (which) points to some kind of Pleistocene legacy, which needs to be explored," he said, referring to the time period that came to an end around 11,000 years ago before the current Holocene Epoch.

Louise Humphrey, a research leader at the Natural History Museum's Centre for Human Evolution Research in London, said she agreed with the study's findings: The Takarkori people were largely genetically isolated for thousands of years, and that pastoralism in this region was established through cultural diffusion, rather than the replacement of one population with another.

READ MORE: Myanmar quake death toll rises amid 'supercharged' suffering

"DNA extracted from two pastoralist women who were buried at the rock shelter around 7,000 years ago reveals that most of their ancestry can be traced to a previously unknown ancient North African genetic lineage," Humphrey said.

She wasn't involved in the research but has worked at Taforalt cave in eastern Morocco, where 15,000-year-old hunter-foragers were buried.

"Future research integrating archaeological and genomic evidence is likely to yield further insights into human migrations and cultural change in this region," Humphrey said.

Christopher Stojanowski, a bioarchaeologist and professor at Arizona State University, said one of the study's more interesting findings was the "inference of a moderately large population size and no evidence of inbreeding."

"That there was little evidence of inbreeding suggests a degree of movement and connection that is also somewhat at odds with the idea of a long-term, disconnected Green Sahara population," Stojanowski, who wasn't involved in the study, added.

Ancient DNA recovery is rare

Experts have studied the skeletons and artifacts unearthed at the site over the years, but attempts to recover DNA from the remains proved elusive.

In 2019, scientists were able to recover mitochondrial DNA, which traces the maternal line, but obtaining this DNA didn't paint the full picture, Ringbauer said.

"A couple of years ago, the samples made their way to Leipzig, because we have continuously fine-tuned new methods over the last years to make more out of a very tiny amount of DNA … and the samples had very little DNA," said Ringbauer, who uses computation tools to analyze genetic data.

Ancient DNA is often fragmented and contaminated.

READ MORE: Markets plunge as Trump tariffs deliver shock waves to world economy

It preserves best in cool environments, not the extreme temperature swings of the world's largest hot desert.

However, Ringbauer and his colleagues at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology were able to extract enough DNA from the two mummies to sequence their genomes, a more complete set of genetic material that allowed geneticists to piece together information about a population's ancestry, not just that of an individual.

"The whole genome carries the DNA for many of your ancestors," Ringbauer said.

"As you go along the genome, you start seeing the different trees of your ancestors. One genome carries the stories of many."