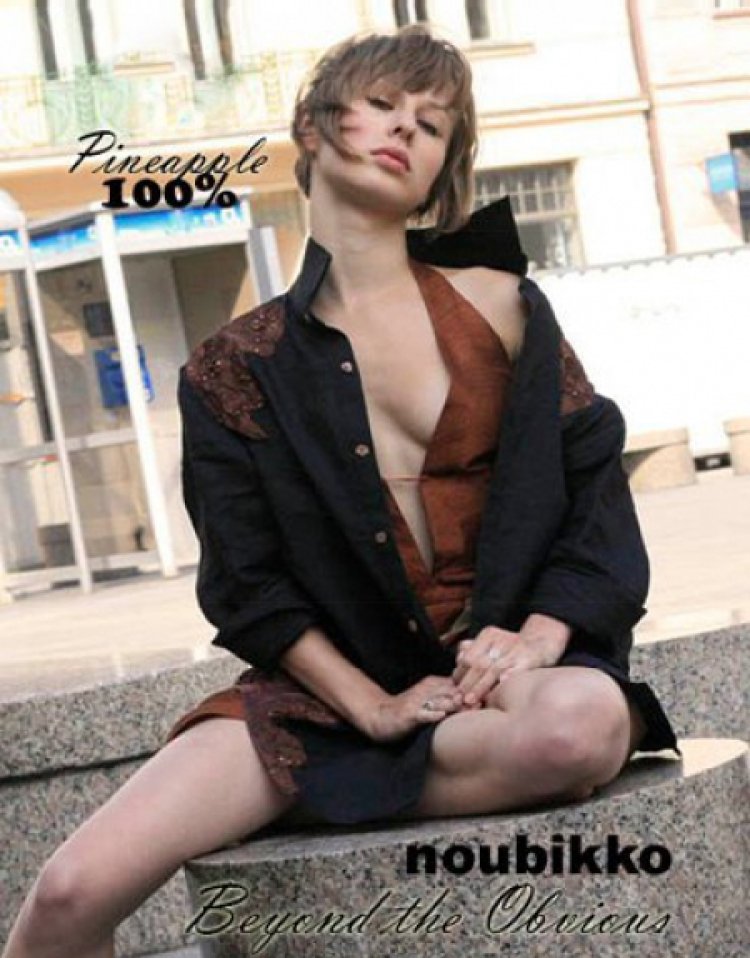

An Open Conversation On Foster Caring, IVF + Being An LGBT Family With Millie & Jessi Poutama

Millie and Jessi Poutama are LGBTQIA+ advocates raising their child in an off-grid community. When the couple decided to start a family, they began fostering a child, before pursuing their own fertility journey three years ago. Their newborn, Tide, was conceived with a known donor and the services of Rainbow Fertility – a dedicated fertility and IVF provider catering exclusively for the LGBTI+ community in Australia. We spoke to the inspiring pair about their experience as foster carers, the IVF process, their expectations of motherhood, and connecting Tide with their donor’s Māori heritage.

An Open Conversation On Foster Caring, IVF + Being An LGBT Family With Millie & Jessi Poutama

Family

LGBTQIA+ advocates and eco-conscious couple Jessi and Millie Poutama are raising their child in an off-grid community. Photo – Alisha Gore for The Design Files.

Their child Tide was born in November 2021 after a three years journey involving donor insemination, miscarriage, and IVF. Photo – Alisha Gore for The Design Files.

Living the most sustainable life possible is important to the family, who have recently moved to an off-grid community on the Central Coast. Photo – Alisha Gore for The Design Files.

Jessi, Millie, Tide and their dogs Moo and Rain. Photo – Alisha Gore for The Design Files.

Millie breastfeeding Tide. Photo – Alisha Gore for The Design Files.

‘Being an LGBT family with two mums means we get to flip the script on what a traditional ‘motherhood’ experience looks like. We try not to compare ourselves too much to others and find a rhythm that works for us.’ Photo – Alisha Gore for The Design Files.

‘We knew we wanted to create a life for our family that was focused around being mindful, living slowly and with purpose, and didn’t feel that we could do that in a conventional setting.’ Photo – Alisha Gore for The Design Files.

‘In terms of what we share online, we have always made a conscious effort to share all of our life – the good and the bad. I think those who have a platform have a responsibility to share authentically, whether that’s us sharing about depression and anxiety, miscarriage, or just the day to day struggles. We hope this comes across to our audience.’ Photo – Alisha Gore for The Design Files.

‘We also made the decision to respond to every direct message on Instagram we get from people who are looking for advice or support or even just want to give us feedback or say hello. If anyone reading this wants to get to know us or learn more, they can contact us.’ Photo – Alisha Gore for The Design Files.

When LGBTQIA+ advocates and eco-conscious couple Jessi and Millie Poutama decided to start a family, they initially thought they’d adopt through foster care. Looking back, Millie reflects, this was a well intended but ultimately naive plan, as the ideal outcome of Australia’s foster care system is always reunification with a child’s birth parents.

Armed with this greater understanding of the system, Millie and Jessi adjusted their expectations and decided to foster regardless. They went on to foster a teenager for two years, who they maintain a close relationship with today.

Jessi and Millie’s journey to later fall pregnant was long and ever changing, involving miscarriage and IVF, before the recent birth of their adorable child, Tide.

Millie joined us for an honest conversation about their parenting journey, from their off-grid community on the NSW Central Coast.

Hi Millie! Thanks for agreeing to speak so openly about your family. Was having children something both you and Jessi have always wanted?

I have always wanted children since I was very young, whereas Jessi wasn’t sure that it would be something she would ever do. It’s important to note though that growing up we just weren’t exposed to LGBTQI+ families in the media, so it was sometimes hard to imagine. The routes to parenthood were also almost non-existent until fairly recently. It wasn’t until 2018 that adoption by same-sex couples was legal in all Australian jurisdictions and laws around same-sex couples accessing assisted reproductive treatments and surrogacy still differ from state to state.

Why did you decide to become foster carers?

We have always wanted to foster and we intend to do it again. Our initial goal was to adopt from the foster care system, which in hindsight was naive at best. The idea of foster care is always reunification with the birth parents, and once we understood that we totally switched our mindset and did it anyway.

[Editor’s note: Adoption of any kind, including from the foster care system, is rare in Australia. Only 264 adoptions were finalised in the entire country over 2020-21, of which only 100 occurred locally with a previous carer not related to the child.]

We have a very close relationship with the girl we fostered from age 14-16, and also with her Mum. Our ability to remain in her life is really a testament to how truly amazing and selfless her mother is. I wouldn’t blame anyone for wanting to close that chapter and move on, but she really welcomed us into her extended family.

Currently, you are not able to foster whilst undergoing fertility treatments [it is generally advised a family’s biological children are at least two years old before welcoming a foster child] so we had to pause for a while.

Is there anything you’d like more people to know about Australia’s foster care system?

Loving the children will be the easiest thing you do. However, I think anyone who is considering becoming a foster parent needs to understand you will often be forced to balance your love for the children with your hatred for the system.

One issue most people don’t know is the number of First Nations children in foster care has doubled since Kevin Rudd’s apology to the Stolen Generations in 2008.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children account for only six per cent of the child population in Australia, and yet make up 37 per cent of children in care. This means they are 9.7 times more likely to be removed from their families than non-Indigenous children. The reasons for this disparity are too complex to do justice here and should be taught by those with lived experience, however poverty, assimilation policies, intergenerational trauma, discrimination and racism as well as forced child removals have all contributed.

When and why did you decide to have a biological child?

I always wanted to carry a baby so it was something we had always talked about. We decided to wait until we got married, not for tradition’s sake, but more as a financial and practical decision.

How was your experience undergoing IVF and falling pregnant?

Honestly, I loved the whole process, but I know that this isn’t the reality for many people. If we hadn’t been successful the first time I might have a different opinion.

We went with a fertility clinic specifically designed for LGBTI+ couples called Rainbow Fertility that made the world of difference. We felt really safe and heard the whole time, which often isn’t the case in medical situations. Something as simple as confirming our pronouns in our first conversation told us it was a safe space for LGBTI+ people.

The IVF process was fairly easy – from our initial conversation to conception was less than six months. However, previous to this we had a number of hurdles. Our initial fertility checks found an 8cm dermoid ovarian cyst that I had removed. They found endometriosis that took two surgeries to remove. We tried to conceive at home first via donor insemination, and ended up getting pregnant, but lost the baby. Our entire fertility journey took over three years.

You used a known donor to conceive your child Tide. Was choosing a known donor important to you?

I want to first make clear that we absolutely support a parent’s decision to use an anonymous donor, but for our family, it wasn’t the right decision.

One thing we took away from foster care is there can be a lot of trauma from not being connected with your biology and history and that it can come with a lot of unanswered questions. We wanted our child to know where they came from.

Does Tide have a relationship with the donor and their Māori heritage?

Yes, absolutely. They are a member of our extended family so they have a relationship with them regardless. We haven’t quite decided how we will navigate the conversations but it’s something we will talk about as soon as they can understand basic language.

Do you have any advice for other people who may be struggling with fertility? How can friends and family support them during this time?

My advice to people going through fertility treatments is that it’s a marathon not a sprint, and to try and think about the end goal and not get lost in the day to day. Easier said than done though!

To those supporting others, I would simply say: listen. Often there is no relevant advice that will help as it’s such an individual experience and it can be lonely for that reason. Sometimes the most important thing is to let someone rant.

How does motherhood compare to your expectations so far?

Being an LGBT family with two mums means we get to flip the script on what a traditional ‘motherhood’ experience looks like. We try not to compare ourselves too much to others and find a rhythm that works for us.

One thing I didn’t expect was being diagnosed with pre and postnatal anxiety. I have never been an anxious person before and I just didn’t see this as being part of my story. Having anxiety has definitely come with its own unique set of challenges and for that reason I try to limit what expectations I have and focus on what I can do, which is mostly love and care for our baby in the best way I know how.

What inspired you to recently move to an off-grid community?

Living a life that’s as sustainable as possible has always been something we have prioritised. We knew we wanted to create a life for our family that was focused around being mindful, living slowly and with purpose, and didn’t feel that we could do that in a conventional setting.

It definitely comes with its challenges and is much more work, from making sure you have dry wood for the wood burner in winter, to making sure that you don’t leave power points on. The house needs a lot of work and maintenance but it’s been really enjoyable. We can’t wait to undertake some renovations soon.

You’ve been very honest on Instagram about your journey to become mothers. How have people responded?

For the most part we always have good feedback, but of course there are always negative or homophobic comments online. It used to affect us a lot more but now we just mostly brush it off. Having a baby did add a layer to this though, as it’s hard to hear negative things said about your child.

In terms of what we share online, we have always made a conscious effort to share all of our life – the good and the bad. I think those who have a platform have a responsibility to share authentically, whether that’s us sharing about depression and anxiety, miscarriage, or just the day to day struggles. We hope this comes across to our audience.

We also made the decision to respond to every direct message on Instagram we get from people who are looking for advice or support or even just want to give us feedback or say hello. If anyone reading this wants to get to know us or learn more, they can contact us.