Alone with You

As cinematic sub-genres go, “the pandemic metaphor” is a legitimate category these days. It has been for quite some time now, ever since last year’s Sundance Film Festival introduced the likes of the trying “How It Ends” and the brilliant “The Pink Cloud”; neither of which are directly about Covid-19, but capture something about the psyche of lockdown all the same. The emergence of this brand of film (or more accurately, the lens in which we interpret them) actually predates Sundance 2021. From Joaquìn Cociña and Cristóbal León’s frightening animation “The Wolf House” to Amy Seimetz’s stylish psychodrama “She Dies Tomorrow,” there were several movies that felt deeply in step with the virus psychology merely months into the plague. Some claimed even “Palm Springs,” an average time-loop rom-com released in the summer of 2020 and had nothing to do with the contagion, seized the loopy repetitiveness of the quarantine. This is all a long-winded way of saying: the pandemic metaphor movies already feel tired, unless they can come up with something new to say or do something other than hammering on, “it’s lonely and claustrophobic and suffocating in lockdown.” This is bad news for debuting feature writer/directors Emily Bennett and Justin Brooks’ barebones “Alone with You,” a claustrophobia-forward horror-thriller, with a predictable “shot entirely during Covid” written all over it. It would have been one thing if “Alone with You” at least worked as a genre outing on some level. It doesn’t—the film’s chills and scares are nearly non-existent; plot, stretched to the seams, unable to sustain a feature's length; and camera work, amateurish. There could’ve perhaps been a zippy little short here, who knows? But that’s not the movie we get. In the 83-minute “Alone with You”—a poor man’s version of “She Dies Tomorrow,” with some David Lynch clumsily mixed in—we are (mostly) alone with Charlie (Bennett), a professional make-up artist waiting for her girlfriend Simone (Emma Myles) to come home to their small, handsomely decorated Brooklyn apartment. Leaving amorous voicemails to her and putting on a silky nightie in preparation for her arrival, Charlie is clearly in love with Simone, an accomplished photographer. But we know something is off in this picture as soon as she drops a glass of red wine into the bubbly bathtub she’s soaked herself in. The filmmakers aren’t exactly restrained about that fact that Charlie doesn’t quite have a sound handle on time. (Oh, these pandemic metaphors…) Through sequences that at best add up to a self-indulgent video project, we follow Charlie as she repeatedly FaceTimes with a close friend who seems to be having a great time at a bar, circles her claustrophobic apartment in changing hairdos and outfits, and keeps topping up her booze supply. In the film’s only dramatically interesting sequence, she takes an emergency video call from her mom (Barbara Crampton), an overly religious, overbearing woman disapproving of Charlie and unsubtly unaccepting of her sexual orientation. After a quarrelsome conversation, Charlie learns about her grandmother’s passing and goes to look for the necklace she’s gifted her on her mom’s request. But wait ... why is it daytime in her mom’s screen? Who is screaming and pleading through the ventilation? Why can’t she see the date or time on her computer screen? And most importantly, why can’t she open her front door or windows? The answers are painfully obvious, but Bennett and Brooks drag the film out anyway, weaving into their narrative inelegant flashbacks about Charlie’s past with Simone as well as a heartbreaking case of infidelity. There are also interludes on a beach and repeated calls Charlie places to 911 in order to be rescued from her place. But help doesn’t arrive. What she instead gets is an escalating sense of madness amid sheet-covered mannequins in her apartment’s dark room and blood-soaked hallucinations. Is she mentally disturbed? Is she already dead? Or has she done something sinister? Again, the film isn’t exactly secretive about the nature of Charlie’s psychosis. Just be warned that you are likely to be disappointed with the fizzling reveal if you’re patient enough to wait for it. Now playing in theaters and available on digital platforms.

As cinematic sub-genres go, “the pandemic metaphor” is a legitimate category these days. It has been for quite some time now, ever since last year’s Sundance Film Festival introduced the likes of the trying “How It Ends” and the brilliant “The Pink Cloud”; neither of which are directly about Covid-19, but capture something about the psyche of lockdown all the same. The emergence of this brand of film (or more accurately, the lens in which we interpret them) actually predates Sundance 2021. From Joaquìn Cociña and Cristóbal León’s frightening animation “The Wolf House” to Amy Seimetz’s stylish psychodrama “She Dies Tomorrow,” there were several movies that felt deeply in step with the virus psychology merely months into the plague. Some claimed even “Palm Springs,” an average time-loop rom-com released in the summer of 2020 and had nothing to do with the contagion, seized the loopy repetitiveness of the quarantine.

This is all a long-winded way of saying: the pandemic metaphor movies already feel tired, unless they can come up with something new to say or do something other than hammering on, “it’s lonely and claustrophobic and suffocating in lockdown.” This is bad news for debuting feature writer/directors Emily Bennett and Justin Brooks’ barebones “Alone with You,” a claustrophobia-forward horror-thriller, with a predictable “shot entirely during Covid” written all over it. It would have been one thing if “Alone with You” at least worked as a genre outing on some level. It doesn’t—the film’s chills and scares are nearly non-existent; plot, stretched to the seams, unable to sustain a feature's length; and camera work, amateurish.

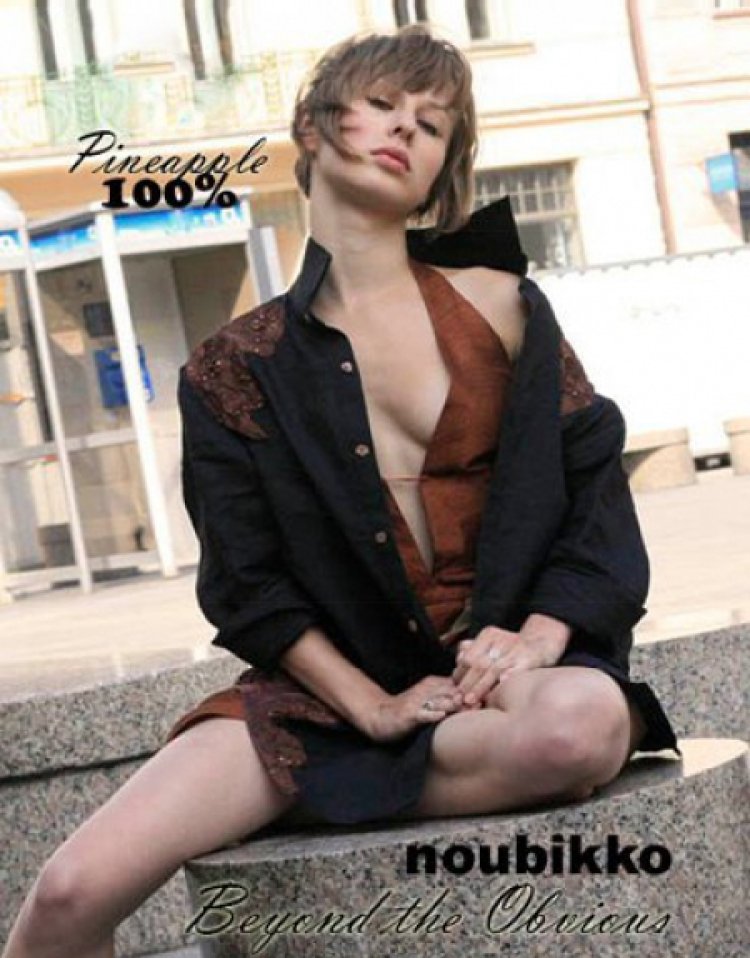

There could’ve perhaps been a zippy little short here, who knows? But that’s not the movie we get. In the 83-minute “Alone with You”—a poor man’s version of “She Dies Tomorrow,” with some David Lynch clumsily mixed in—we are (mostly) alone with Charlie (Bennett), a professional make-up artist waiting for her girlfriend Simone (Emma Myles) to come home to their small, handsomely decorated Brooklyn apartment. Leaving amorous voicemails to her and putting on a silky nightie in preparation for her arrival, Charlie is clearly in love with Simone, an accomplished photographer. But we know something is off in this picture as soon as she drops a glass of red wine into the bubbly bathtub she’s soaked herself in. The filmmakers aren’t exactly restrained about that fact that Charlie doesn’t quite have a sound handle on time. (Oh, these pandemic metaphors…)

Through sequences that at best add up to a self-indulgent video project, we follow Charlie as she repeatedly FaceTimes with a close friend who seems to be having a great time at a bar, circles her claustrophobic apartment in changing hairdos and outfits, and keeps topping up her booze supply. In the film’s only dramatically interesting sequence, she takes an emergency video call from her mom (Barbara Crampton), an overly religious, overbearing woman disapproving of Charlie and unsubtly unaccepting of her sexual orientation. After a quarrelsome conversation, Charlie learns about her grandmother’s passing and goes to look for the necklace she’s gifted her on her mom’s request. But wait ... why is it daytime in her mom’s screen? Who is screaming and pleading through the ventilation? Why can’t she see the date or time on her computer screen? And most importantly, why can’t she open her front door or windows?

The answers are painfully obvious, but Bennett and Brooks drag the film out anyway, weaving into their narrative inelegant flashbacks about Charlie’s past with Simone as well as a heartbreaking case of infidelity. There are also interludes on a beach and repeated calls Charlie places to 911 in order to be rescued from her place. But help doesn’t arrive. What she instead gets is an escalating sense of madness amid sheet-covered mannequins in her apartment’s dark room and blood-soaked hallucinations. Is she mentally disturbed? Is she already dead? Or has she done something sinister? Again, the film isn’t exactly secretive about the nature of Charlie’s psychosis. Just be warned that you are likely to be disappointed with the fizzling reveal if you’re patient enough to wait for it.

Now playing in theaters and available on digital platforms.